When I started my practicum at the Champaign County Historical Archives, I did not know what to expect, but I wanted to round out my studies and gain valuable experience in archives.

When applying to the practicum position I expressed interest in the 1858 Bowman Map of Urbana and West Urbana, and I’m glad I did, as I was assigned to expand the map’s digital exhibit to include the 1863 Champaign County Map, also by Bowman.

I initially expressed interest in the 1858 Bowman Map of Urbana and West Urbana and was assigned to expand on the map’s digital exhibit to include the 1863 Champaign County Map, also by Bowman.

To begin my research, I listed every building and person that were highlighted on the border of the map. Then, I referenced the 1858 version to see which buildings and people were on both maps. I decided not to research places like Angles Block or people like J. S. Wright, as they were already covered in the existing exhibit. With this in mind, I had an outline of the remaining buildings and people left to research.

I chose the First Presbyterian Church of Champaign as my first topic. By searching in the Archives’ catalog, Local History Online, I found several books on the church. Unfortunately, not every building or person were so well documented. Some subjects were much more difficult to research. After taking thorough notes of the materials on the church, I shifted my focus to Homer Seminary, a building on the top left corner of Bowman’s map. There was nothing to find in the catalog. I found one mention of a Seminary in Homer in J. O. Cunningham’s “History of Champaign County,” a valuable resource that contained much of the information I included in the exhibit. It was a short description of the difference in the education system in the county to the Free School law. I knew then that every topic could not be included in the exhibit.

I moved on to research the Champaign County Courthouse. J. O. Cunningham had mentioned several early iterations of a courthouse in the county. The first cases were heard in private residences of judges due to a lack of a permanent building. Finally, the courthouse depicted on the Bowman map was built. Bowman himself was the architect and supervisor of the project. This building was a more permanent version of a courthouse, built for $30,000 and finalized for use in 1861, two years prior to the 1863 county map. It was the center of a fevered controversy in the county. Cunningham briefly mentioned this controversy in his book. The two cities at the time – Urbana and West Urbana – were vying for the county seat. West Urbana’s population had exploded, making them a commercial epicenter in the county. They were expecting more of a debate over the courthouse location, but County Board leaders quickly decided to build in Urbana, leaving no room for the growing West Urbana’s input. This angered two newspapers in West Urbana and they began publishing harsh articles about the Board and its members. Cunningham described an altercation between West Urbana residents and a member of the County Board, where the residents egged the Board member’s carriage when they were entering the city.

This of course intrigued me, could the person who was egged be someone of note on the border of the 1863 map? I took the name of the newspaper from Cunningham’s book, the Urbana Clarion, and I began digging. Using the microfilm of the Urbana Clarion, of which the archives had one reel of film for, I found the exact article describing the egging. The person who was egged? Fielding L. Scott, whose residence is on the border of the 1863 map. Not only was he egged, but he also retaliated by beating the group leader with a rawhide. Scott himself was fined more for this action than the original egging leader. This was an incredible find of1860s shenanigans that could be included in my exhibit, all surrounding a building that the map creator designed himself.

After this discovery, I began seeing the names I was looking at on the map over and over again in my outside life, and having other “aha” moments. For example, Wright St., a street named for J. S. Wright, or Coler Crossing, an apartment building whose namesake, Col. W. N. Coler, was a prominent pioneer in town.

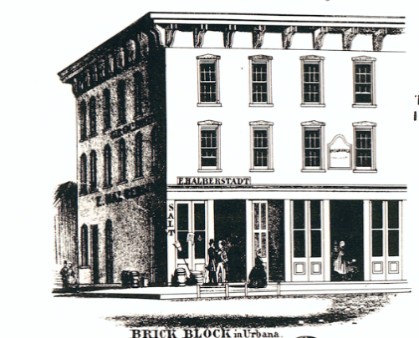

Illustration of the Brick Block from the 1863 Bowman Map.

I have been walking through Mount Hope Cemetery with my dog since I started school here two years ago. It is a serene location with fewer dogs and people to worry about, so my dog really enjoys this setting for our walks. Little did I know that an invisible string would lead me to not one, not two, not three, but four graves of individuals depicted on the map I was researching. I remember a specific day at the Archives where I scanned around 10 images of B. F. Harris for my exhibit. That afternoon, I walked and found his exact burial location. Without prior knowledge, he was buried in the cemetery, the man I was researching and scanning images of was right before me. It was a surreal feeling.

I also found the graves of Rev. Gerald Riley and William D. Somers right next to each other on my usual path. Finally, I found Eli Halberstadt, whose residence was not depicted on the map but whose commercial building Brick Block lists his name. This building did not come with many mentions in the catalog, so it is not detailed in my exhibit, but still a name I have come in contact with several times as I researched. I want to emphasize that the locations of the graves are available in the Archives, but I was never focusing on these sites for my research, so I never actually looked into where these people were buried. I just found them organically while walking my dog.

After these moments, I finalized my research with the catalog and settled on who I would include in the exhibit. There are 10 people, those of which I could find good descriptions of as well as some form of artifact to include. These were mostly illustrations of the people, as portraits were very expensive at the time. I wrote the entries for the exhibit and added the items collected into Omeka. These entries were edited and I built the online exhibit. Omeka makes this process super intuitive, all the users have to do is use the content blocks and adjust as needed. This process gave me valuable insight into the inner workings of Omeka as a platform, a skill I will certainly need as I continue as a librarian.

I have never felt so connected to a place as I have while researching this county map. These little moments of quiet discovery outside of the library floored me. I am so glad that I could not only research and curate this exhibit, but share those little moments through this post as well.

-Chloe Miller

Practicum Student