During recent park improvements, undertaken in 2020, portions of ten gravestones from the Old Urbana Burying Ground were unearthed in Leal Park. Work ceased on the project to add additional parking spaces and an accessible path to the administration building, while the Public Service Archaeology & Architecture Program from the Department of Anthropology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign assisted the Urbana Park District in complying with the State of Illinois laws regarding the protection of cemeteries. Work on the park improvements resumed, and the Public Service Archaeology & Architecture Program provided the Archives with information and digitally enhanced photographs from the project.

Legible information on the stones is varied due to stone condition and missing pieces. Names on the headstones include Hannah, wife of Thomas, Rachel E. Hogwood, Suscelia A. Hogwood, Isabella E. Hyde, Jonathan Sherman, Delbert H. Sutton, Marshall Sutton, George A. Whisman, Abner C. Wyatt, and Florance A. Wyatt. You can view photographs of the gravestones on our Flickr album, “Old Urbana Burying Ground.” Archives staff have added additional information to the images gleaned from the stones themselves and from research within our collection.

Legible information on the stones is varied due to stone condition and missing pieces. Names on the headstones include Hannah, wife of Thomas, Rachel E. Hogwood, Suscelia A. Hogwood, Isabella E. Hyde, Jonathan Sherman, Delbert H. Sutton, Marshall Sutton, George A. Whisman, Abner C. Wyatt, and Florance A. Wyatt. You can view photographs of the gravestones on our Flickr album, “Old Urbana Burying Ground.” Archives staff have added additional information to the images gleaned from the stones themselves and from research within our collection.

The Old Urbana Burying Ground was not officially plated as a cemetery, and anyone could be buried there. No records or lists are known to exist with the names of everyone who was buried. The graveyard was most active from 1834-1870. On March 7, 1870, the special committee on cemetery ordinances reported to the Urbana City Council in favor of adopting Mount Hope Cemetery as the city’s burying ground. At the same meeting, a resolution was made by Alderman Russell and adopted that the old burying ground commonly called the “Old Grave Yard” be declared vacant, and “all persons having friends therein buried are requested to removed them.”

Although many of the bodies were moved to other cemeteries, the old Urbana Burying Ground remained until 1903 when Col. Samuel T. and Mary E. Busey deeded the burial ground over to the city with the condition that the land be used as a city park. At this time, more than 125 families of people buried in the old graveyard were contacted. In some cases, the families instructed that the gravestone be buried, others wanted only the gravestone moved, and still, others had the remains moved to other cemeteries, mainly Mount Hope. It is estimated that thirty to forty graves remained on site. The remaining markers were laid flat and covered with dirt.

The information found on the uncovered gravestones provides documentation that previously might not exist anywhere but in a family Bible, passed down oral family histories, or possibly on a stone in a different cemetery where the remains were removed. Death records were not recorded with the Champaign County Clerk prior to 1878. Even after recording began in 1878, not all deaths were reported, and early newspapers seldom printed obituaries.

As Archives staff discovered in researching these gravestones, in some instances, the information on the new stone might not agree with the information on the stone from the Old Urbana Burying Ground. Maybe the stone was carved incorrectly, the family forgot the date of death, or a relative wanting to memorialize a family member had only vague childhood memory of the death or gave the name a different spelling based on their oral history of the name.

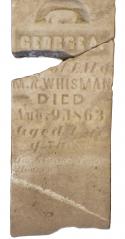

In the case of the gravestone for George A. Whisman, a vital piece of information is missing from the stone. Would this missing piece of the stone have said son or dau [daughter]? In Mount Hope Cemetery, there is a four-sided Whisman family stone with the year 1891 on the base. On this stone, the name is given as Georgia A. Whisman, with the same death date and age as George A. Whisman found in Leal Park. So is this the same person as George A.? There was only one Whisman family listed in the 1870 census for Champaign, which was after George A. or Georgia A. would have died. A child dying on the same date, with the same age and surname, would seem unlikely.

In the case of the gravestone for George A. Whisman, a vital piece of information is missing from the stone. Would this missing piece of the stone have said son or dau [daughter]? In Mount Hope Cemetery, there is a four-sided Whisman family stone with the year 1891 on the base. On this stone, the name is given as Georgia A. Whisman, with the same death date and age as George A. Whisman found in Leal Park. So is this the same person as George A.? There was only one Whisman family listed in the 1870 census for Champaign, which was after George A. or Georgia A. would have died. A child dying on the same date, with the same age and surname, would seem unlikely.

Seven of the ten stones were for children under the age of ten, and only one of the children would have been alive when a census was taken. There were very few newspapers available for the 1855-1866 period. Early newspapers were mainly advertisements, national stories, editorial letters, and governmental happenings. Death notices and obituaries were seldom found unless the death involved a tragedy, murder, suicide, accident, war, or the person was a prominent member of the community. Deaths notices for women and children were scarcer. The only person from the uncovered gravestones who was mentioned in the local newspapers was A.C. Wyatt. A proprietor of the Champaign House, he died after being kicked in the head by a horse. There is no mention in the newspaper of his assumed daughter, Florance A. Wyatt, who died twelve-days after him.

There is no definite information on Jonathan Sherman. He may be connected to the Wyatt family, but this has not yet been proven. Information for families on the remaining stones is limited to census records that occurred either before the person was born or after the person's death listed on the stone.

As you can see from this account, genealogy research can often involve a bit of detective work. If you need help researching your family history, the Champaign County Historical Archives is here to help.

- Karla Gerdes

Archives Assistant