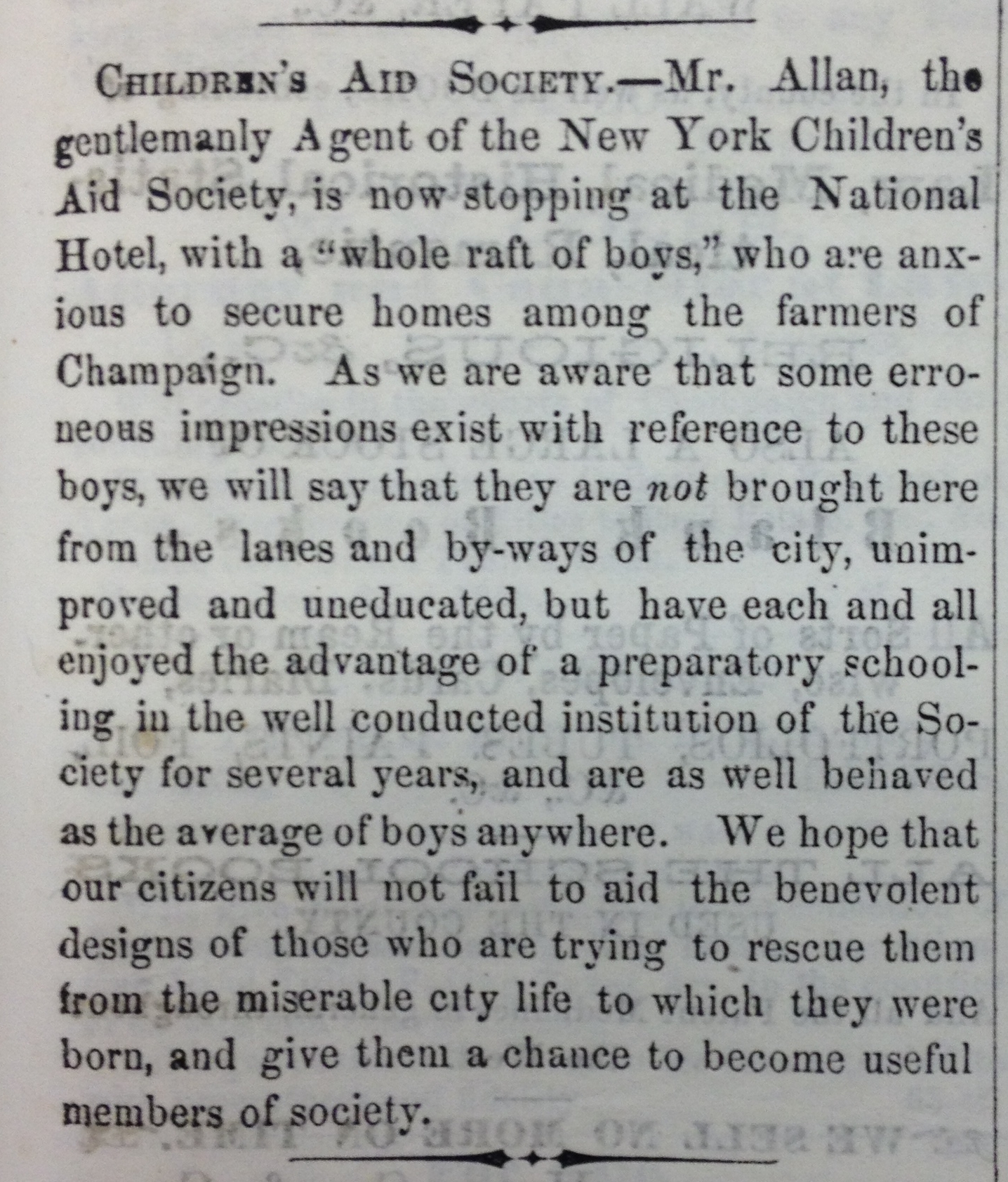

By the middle of the nineteenth century, New York City was teaming with new immigrants, with more coming every day. These new families often found themselves in dire circumstances, surrounded by poverty and disease. As a result, many children ended up without parents, orphaned and left wandering the streets. The plight of these children did not go unnoticed, and soon several orphanages and aid societies developed to assist them. Some, such as Charles Loring Brace of the Children’s Aid Society, believed that the best way to help these unfortunates was to remove them from the dirty, disease-ridden streets of New York to the comparatively clean, morally upright farms of the Midwest. Other agencies, such as the New York Juvenile Asylum and the New York Foundling Hospital came to the same conclusion. Soon agents fanned out across the states of the Midwest, offering children for indentured work on farms. Eventually they made their way to Champaign County. An advertisement in the September 14, 1859 edition of the Central Illinois Gazette stated:

Trainloads of children, soon known as the “Orphan Trains,” began heading west. By the time the last train left New York in 1929, some 200,000 children were sent to new homes. Between 1855-1898, The New York Juvenile Asylum alone sent 6000 children to Illinois.

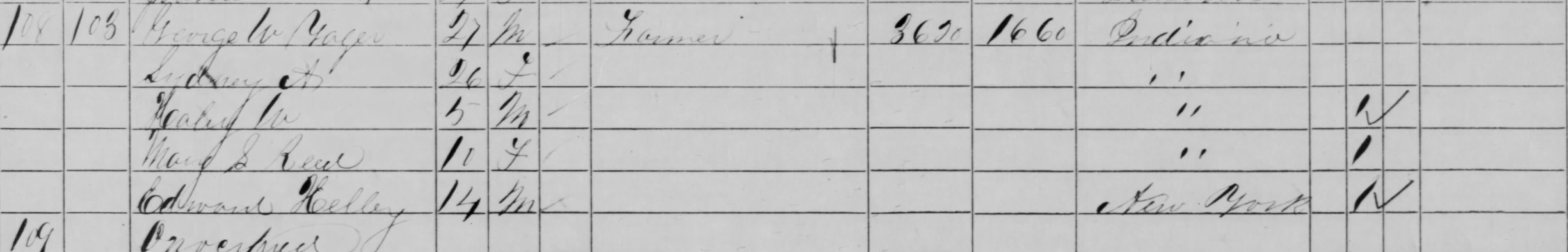

Many of these institutions entered their wards into formal indentures with heads of households. These indentures set formal terms: a specified trade to be learned, length of contract, and payment at the end of the term. Edward Kelly, a ward of the New York Juvenile Asylum, was entered into this indenture with George Yeager for the term of six years and ten months. These children would then be a regular part of the household, as seen in this entry in the 1860 Federal Census [George "Yager" and Edward "Kelley"]:

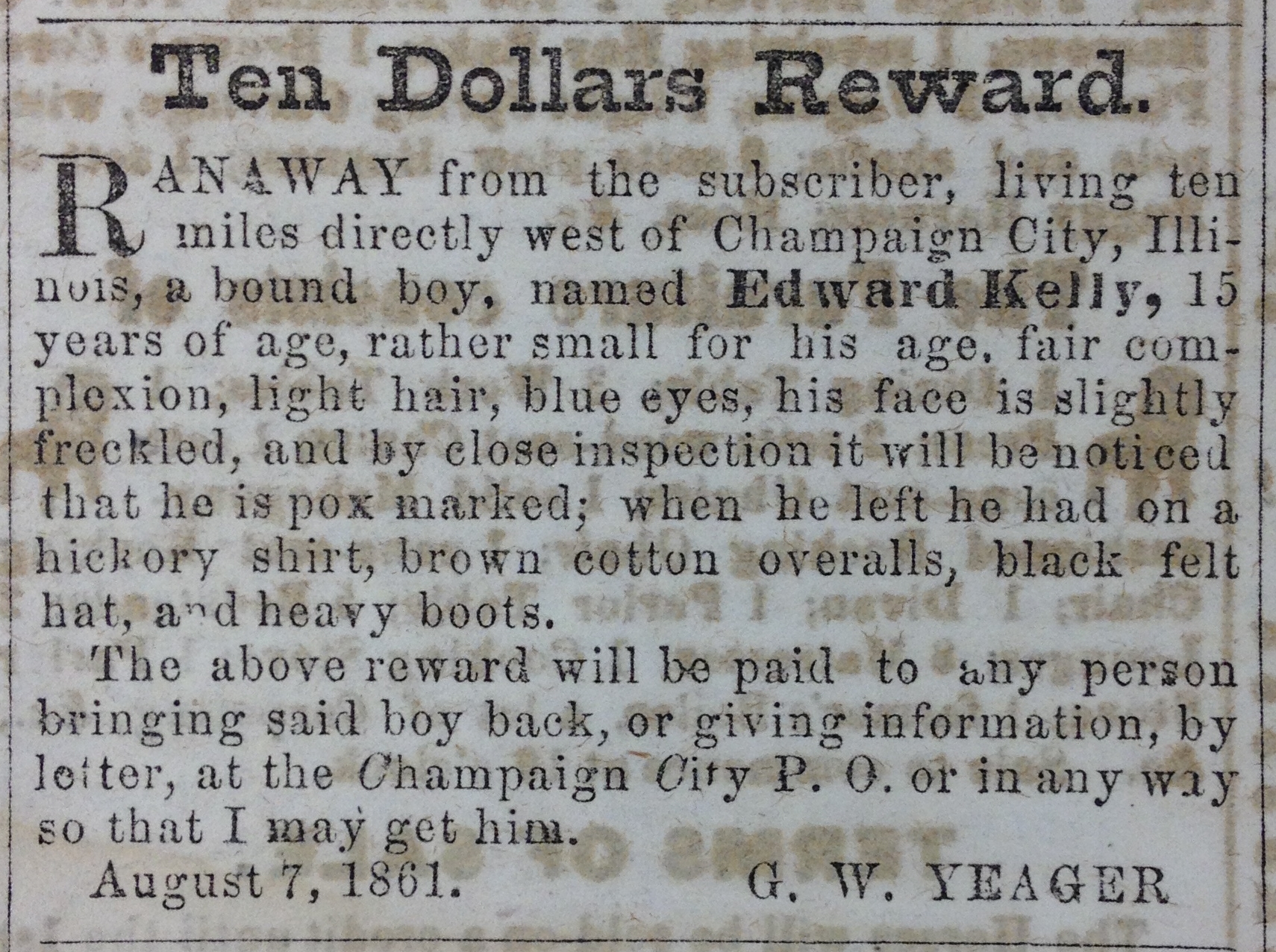

Many times these orphans would successfully complete the terms of their indentures, remain locally, and start and raise families of their own. James Robertson offers one such case. When the Civil War broke out, he ran away from his indentured home to enlist in the army. He returned to Champaign County after the war, married, bought a farm, and raised six children of his own. Edward Kelly’s case was a little less successful, as demonstrated by this notice in the August 7, 1861 edition of the Gazette:

We have many records of the “Orphan Train” children here in the Local History and Genealogy Department, including the original copies of many of the indentures. Stop by soon to learn more!