So, what do archivists do? Here at the CCHA, we have a clever meme in our office that explains how the different people in our lives imagine our occupation. It suggests our friends believe we are surrounded by a mess of old books in stuffy stacks, that our family sees us as old curmudgeons browsing through dusty tomes, and that society sees us as genealogical wizards. While some of these characteristics are true to some extent, what we actually do is more nuanced, varied, and interesting.

So, what do archivists do? Here at the CCHA, we have a clever meme in our office that explains how the different people in our lives imagine our occupation. It suggests our friends believe we are surrounded by a mess of old books in stuffy stacks, that our family sees us as old curmudgeons browsing through dusty tomes, and that society sees us as genealogical wizards. While some of these characteristics are true to some extent, what we actually do is more nuanced, varied, and interesting.

A recent reference request to the archives from the News-Gazette’s Tom Kacich offers a great example of how our days are filled. Kacich asked a seemingly innocuous question that appeared to have a straightforward answer, but when I began my research, I found that the answer was not easy to locate. On February 12, I entered work and was immediately presented with the question, “Where did Race Street in Urbana get its name?” Being a part of the archives for the last two and a half years, I quickly responded with the answer I had been told many times. “Because people used to race down the street.” Our librarian said, “Ok, but can you prove it?”

I could not help but smile at her response. She was correct. We all heard the story, but where did it come from? Was it actually true? I began my research by consulting some of our most well-used county histories, but sadly neither Cunningham nor Stewart were able to help with my question. I went back to the stacks and browsed the other available histories and found an old thesis from 1937 by U of I graduate student and local historian Natalia Belting. According to a footnote in Belting’s thesis, “there is no record of the person responsible for the naming of the streets in the new town (Urbana). But those names given in the plat of the Town of Lancaster, laid out in July, 1832 by Noah Bixler, are the names that were a year later bestowed upon Urbana streets.”

This was my first real lead. From here, I tried to find more information about Lancaster, but I was not able to discover anything from the Champaign County sources, so I turned to the internet. Through a basic Google search, I found that Lancaster was not part of Champaign County, but was actually in nearby Vermilion County. Using this information, I pulled one of our sources on Vermilion County, and sure enough, in the chapter about abandoned towns, I found half a paragraph that said there was a town named Lancaster founded by Noah Bixler.

This was my first real lead. From here, I tried to find more information about Lancaster, but I was not able to discover anything from the Champaign County sources, so I turned to the internet. Through a basic Google search, I found that Lancaster was not part of Champaign County, but was actually in nearby Vermilion County. Using this information, I pulled one of our sources on Vermilion County, and sure enough, in the chapter about abandoned towns, I found half a paragraph that said there was a town named Lancaster founded by Noah Bixler.

This information seemed to verify that there had been a town called Lancaster. Still, there were only two sources that stated this, and the Belting thesis referenced the Vermilion County history book as its source, so really, we only had one source. Knowing that this type of land purchase would’ve been recorded, I reached out to the Danville Public Library and asked their archives department if they were familiar with Lancaster. They were not, but were just as eager to find out about this mystery as we were in Champaign County, so they started researching the question, as well.

While we waited to hear back from Danville, I decided to do some research on the name ‘Race Street’ in general. I found that it was a commonly used name for streets in early American history along with other streets like ‘Washington,’ ‘Market,’ and ‘Main’ streets. Market and Main derived their names from the activities done on those streets, and it seemed Race Street did as well. In Philadelphia, for example, Sassafras Street was renamed Race Street in 1800 because citizens regularly used it for horse racing. Interestingly, Race Street in Philadelphia runs perpendicular to Cherry Street, and in Urbana, Race Street runs perpendicular with Cherry Alley.

By the time we heard back from Danville, it had been about four hours. While we tirelessly worked to find the answer to Kacich’s question, they were working just as hard one county over. They found that there was a town of Lancaster and that the grantee and grantor indexes could prove it. Still, they did not have those records because the abandoned town was not within the boundaries of Vermilion anymore; it was in Champaign County. As a result, the Champaign County Recorder’s office held the information, not Vermilion County. Danville informed us they would follow up with the information regardless, and sure enough, we received an e-mail about a week later with scans of the grantee and grantor indexes that proved the existence of Lancaster, but there was not a plat in the index book. To find that, we needed to consult the deed books. Again, this took a few days, but sure enough, this information eventually came through, and we received a scan of the plat of Lancaster, founded in 1832, just one year prior to Urbana.

As Belting suggested in her thesis, the layout of Lancaster was shockingly similar to Urbana, but unfortunately, there was no actual evidence to support the claim that Urbana took its plat from Lancaster. We are only left with scattered evidence, potential answers, and an ongoing mystery, but our research was not done in vain. We may not have the actual answer, but we have a great story filled with intrigue and a ready response for anybody seeking information on Urbana street names in the future.

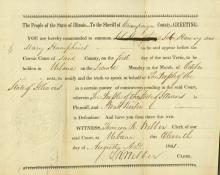

As a final note, I will mention that this was not my first run-in with Vermilion County’s Noah Bixler. Once I saw his name, I could not help but think I had seen it before. At the beginning of December 2019, I decided to go through the county’s oldest criminal court records that we have on file for a potential blog post. Sure enough, the second criminal court record we have on file is from the summer of 1841, and Noah Bixler was arrested for assault.

As a final note, I will mention that this was not my first run-in with Vermilion County’s Noah Bixler. Once I saw his name, I could not help but think I had seen it before. At the beginning of December 2019, I decided to go through the county’s oldest criminal court records that we have on file for a potential blog post. Sure enough, the second criminal court record we have on file is from the summer of 1841, and Noah Bixler was arrested for assault.

- Tom Kuipers

Archives Assistant