On September 17, 1947, a 7-car train left Philadelphia to embark on a 37,000-mile trip. The train, painted white with red and blue horizontal stripes, carried 133 historical documents and artifacts of United States history. The historic cargo ranged from a 15th-century Christopher Columbus letter to Germany's 1945 letter of surrender signed just a few years before the train's departure.

The Freedom Train was described as "… a campaign to sell America to Americans." It was also one of the first attempts to "articulate a national identity and define citizenship after the New Deal and World War II." [1] Of course, this curated story of America left out several groups.

The original plan was to have Congress fund the Freedom Train. However, when the organizers were unable to secure appropriated funds, the American Heritage Foundation was created to lead and finance the Freedom Train Project. [2] The Foundation was a non-partisan, non-profit group that was heavily populated by corporate CEOs and Hollywood financers. The Foundation's Board of Trustees admitted a single African-American member, Frederick D. Patterson, after the train launched in 1947.

The National Archives provided one-fourth of the exhibit's documents. [3] The other historical items came from the Library of Congress, government agencies, and private collections. The National Archives was responsible for gathering, physically assembling, and preparing the exhibit materials for travel and exhibition. [3] Elizabeth Hamer, Chief of the Division of Exhibits and Publications at the National Archives, presented the American Heritage Foundation with a list of documents selected by National Archives staff.

The staff recommended documents covering women's suffrage, collective bargaining, Franklin D. Roosevelt's Executive Order 8802, and the National Labor Relations Act. The Foundation was unhappy with the list because it "detracts from our objectives." In April 1947, the Foundation rejected The Archives' list and gained control of document selection with the creation of the Documents Approval Committee. [1]

In the end, the only document included pertaining to black history was the Emancipation Proclamation. Labor history, women's history, and civil rights were also underrepresented as the Foundation declined to "include documents that were the subject of current legislative consideration or were deemed to be of a partisan or controversial nature." [3]

Despite the controversy surrounding the funding and document selection, the Freedom Train was presented positively in the mainstream press and local communities. The Freedom Train arrived at the Illinois Central depot in Champaign at 3:00 am on Friday, July 16, 1948. Champaign was the train's 232nd stop. By 8:30 am, the four-abreast line "was wrapped around the north end of the Illinois Central station and about one-fourth of the way down the station. By 11 o'clock, the line was still four-abreast, extended down Chestnut street, and all the way under the University avenue viaduct." [4]

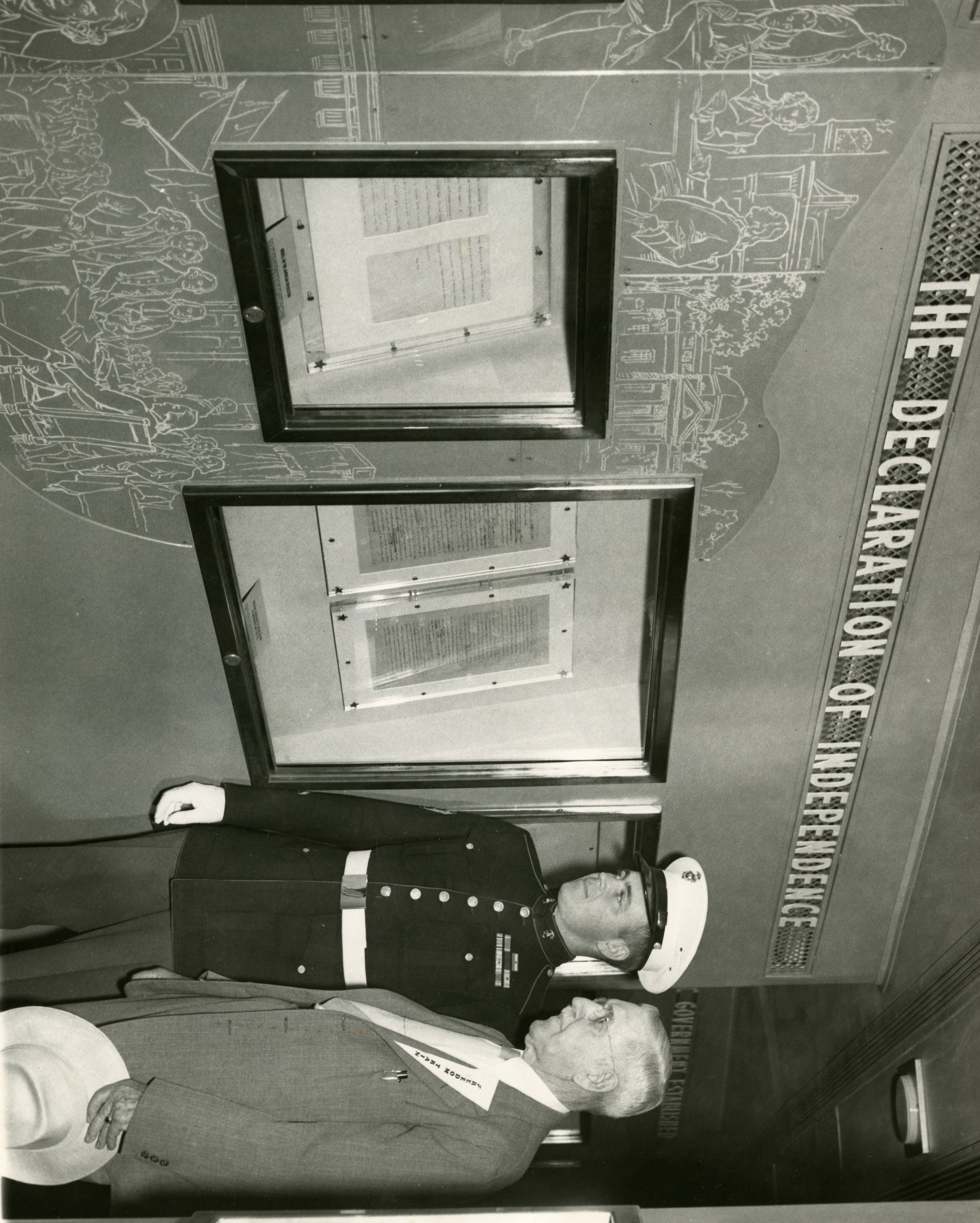

The crowds did have entertainment with speeches from local leaders and pastors and from Walter H. S. O'Brien, director of the train. Chanute Air Force Base provided two airplane salutes at 11:00 am and 12:00 pm, and local orchestras furnished background music throughout the day. The train was on display from 10:00 am to 10:00 pm, and 7,214 people ultimately passed through to see the historical documents on display. [5]

Although, how much people were able to interpret and fully appreciate the documents is up for debate. The Courier printed:

"Overheard on the Freedom Train: An elderly lady, being gently nudged along by the long line of people, remarked to her companion. "It sure is interesting, but to get anything out of it, you'd have to spend hours."

The other lady answered: "I know. You've got time to see the item and read the big letters." [4]

By late Friday evening, the Freedom Train was on the move again, traveling to Decatur and on to Springfield. All told, the Freedom Train was visited by 3.5 million people in 322 cities in all 48 states (Alaska and Hawaii were not states at the time) during its 413-day journey. [3]

The Freedom Train's tour ended on January 24, 1949. A month later, Congress drafted legislation to put the train back into operation, but funding could not be acquired, and the train tour was not resumed. The Freedom Train did make a second appearance during the nation's bicentennial in 1975-1976.

- Sherrie Bowser

Archives Librarian

[1] Little, Stuart J. 1993. “The Freedom Train: Citizenship and Postwar Political Culture 1946-1949”. American Studies 34 (1):35-67. https://journals.ku.edu/amsj/article/view/2850.

[2] Nieuwsma, Alex and Emma Rothberg. “Freedom Train | U.S. National Archives.” https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/freedom-train-u-s-national-archives/wQqYDx49?hl=en

[3] Bradsher, Greg. 2020. “The Freedom Train, 1947-1949”. The Text Message. https://text-message.blogs.archives.gov/2020/04/07/the-freedom-train-1947-1949/

[4] “Crowds Arrive Two Hours Early to See Freedom Train Exhibits.” Champaign-Urbana Courier. 16 July 1948.

[5] Photo caption. Champaign-Urbana Courier. 18 July 1948, p. 11.